Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Ever heard of them? That’s what I thought. Let’s get right into it:

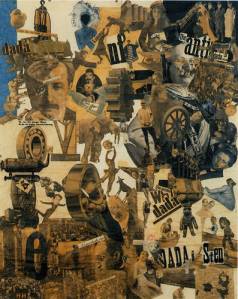

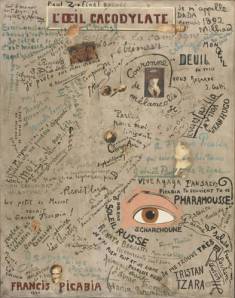

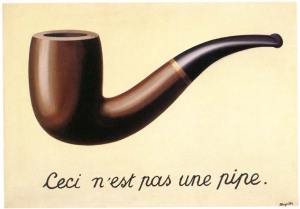

Text in art till the mid-late 50’s had at best been an element in a larger composition, never quite the central aspect of the work. Duchamp fiddled about with the use of text for the occasional goof, but these goofs took some explaining. Ono, Ruscha, On Kawara and a host of others changed all that, using text as the literal medium/object of the work such that the idea of what art might become was forever changed. Not bad, eh?

But even with this revolution underway there remained an inherent mistrust of the use of images and language in tandem. Art had accepted single words (Ruscha), brief sentences (Ono) and the occasional amalgamation falling somewhere inbetween (Indiana), but what about work that pointed to something a bit more complex, yet harkening back to something far more sinister?

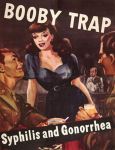

Before we dive into all that, let’s look again at those crazy images kids of the 40’s and 50’s had been hammered with:

War, domesticity, cultural correctness and fear. Do this and you’ll survive. Do that and you’ll die. There’s no room for ambiguity in this equation, no nuance and certainly no %&#@ questioning of the Almighty Authority lest you be labeled a pervert, communist, intellectual, snob, square, Beat or Red. Happy Days was bullshit.

So now instead of rebelling against those messages, Warhol appropriated the most banal example he could find (Campbell’s Soup Can) and Lichtenstein picked up the escapist imagery of comic books that kids of multiple generations turned to as an entertaining alternative to the pressures of growing up, aka: the constant bombardment of cultural propaganda (Whaam!). Freaking radical, sure, but a radical use of text in art? More so a necessary requirement, which is the real innovation here.

Here’s how it works:

Warhol’s use of text in the Campbell’s Soup Can is an essential identifying aspect of the art, but it isn’t the fundamental point of the art, though granted there’s no Campbell’s without Campbell’s. Warhol painted a mass-produced can of soup. The can requires text. Thus text is used to faithfully represent the can. Further, Warhol’s use of text doesn’t really signify the use of text in the same way Ono, Ruscha or Kawara used it. It’s akin to how Picasso or Schwitters used it, as a collage element (written by someone else) essential to the piece they were creating. The central aspect and end result, to my way of thinking, is that it’s a modern day still life, a winking reflection of the times. Or, better yet, a portrait.

Lichtenstein’s use of text is essentially identical. That it has an aesthetically pleasing Pop form is a real bonus, making is more commercially accessible than, say, Lawrence Weiner. More importantly, both text and image are appropriated, turning the artist, via the use of low brow imagery, into a high brow critic of culture. The use of text + image has been sterilized, offering something harmlessly fluffy in return. That’s a smart bit of work, actually, allowing text to crawl back into bed with image without the child it bears telling you that you’re doomed. I imagine it had to be a massive relief, really, for all those former kids trudging home from their endless 9-5’s with briefcase and Fedoras, wives prepping TV dinners in their suburban homes with 2.5 kids begging for attention, seeing Drowning Girl in Leo Castelli and laughing hysterically all the way home.

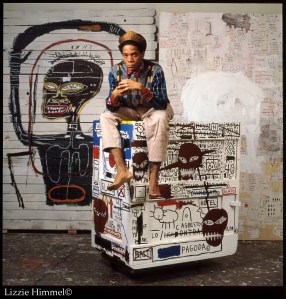

Which perhaps at some point leads to Christopher Wool’s Apocalypse Now (or Tom Waits’ Franks Wild Years), but we’ll get to that soon enough. In the meantime a preview!